Messiah of Evil

Day 5 of my 31 Days of Horror viewing

For the last few years, I have used October to give myself a viewing assignment: a different horror film each day. Now that I have escaped the real life horror of New Zealand’s public service, I intend to write a piece inspired by each film.

My fifth film is Messiah of Evil (1974) co-directed by Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz.

Every now and then, someone will tweet an image from The Wizard of Oz and say something like “I can’t believe this movie influenced David Lynch’s entire career.” Even if they’re being reductive, they’re not exactly wrong—the movie was clearly a big influence on Lynch. However, I’d like to humbly suggest that Messiah of Evil also feels like a key text in understanding his work. It’s hard for me to believe that he’s never seen this.

In one of its earliest scenes, Arletty (Marianna Hill) drives down a California highway at night on her way to the town of Point Dume to visit her father and we’re treated to a ‘car’s point of view’ shot. This is a shot I will always associate with Lynch for the way it so effectively builds dread in works like Lost Highway and Twin Peaks: The Return. From the moment she arrives, the sound of waves crashing on the Pacific Coast is near incessant, providing a backdrop to most of the horror during the film. Moreover, there is something Lynchian about how stilted dialogue, inconsistent eyelines and 'crossing the line’ are used to convey a sense that something is off, even if you can’t always put your finger on it.

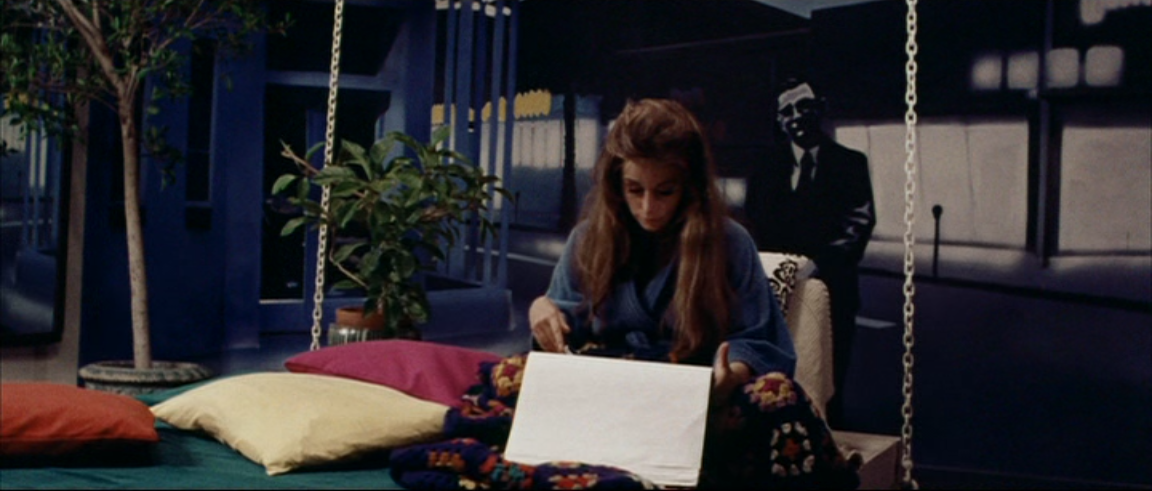

Once she reaches Port Dume, Arletty’s primary interactions are with other visitors from out-of-town. Thom (Michael Greer) is a Portuguese-American dandy and his companions Toni (Joy Bang) and Laura (Anitra Ford) bring to mind Manson girls more than anything else. This counter-cultural throuple are interlopers that the conservative town’s sinister squares must do away with like white blood cells. As Thom observes at one point, “If the cities of the world were destroyed tomorrow, they would all be rebuilt to look like Point Dume, entirely normal, quiet. Silent, though, because of the shared horror... I know what's hiding now beneath its stucco skin.” Again, this idea of something evil lurking below an all-American façade is pure Lynch.

In American pop culture, the years following the end of the sixties were characterised by disillusion, as if all the hope of that decade was leaking out from the cracks in society. So many films of this time are suffused with a sense of stasis preceding the reactionary correction of the following decade. And what better place to demonstrate this feeling than the Pacific coast of California—where the dream of westwards expansion reached its own limits 100 years earlier. Messiah of Evil makes explicit the connection between these two historical moments, each marking the end of a time of hope, by centering its supernatural menace on a dark figure who would return to the town from the sea after the intervening century.

Different historians have described various historical events as moments that would have felt like the end of the world for those who experienced them. For most of Europe, the Black Death was a time of apocalypse. Similarly, Indigenous peoples have endured apocalyptic encounter after apocalyptic encounter with colonising forces. This violence continued through the 1870s when American colonisers reached their own world’s end. And then, the end of the hippie dream must have felt apocalyptic for burnt out Californians in the 1970s—it’s no coincidence that this was a golden age for doomsday cults. I love this film for the way it draws these historical connections, especially as we are living through another moment that feels apocalyptic.

Port Dume is every town in America. Its residents are prepared to turn on the visitors like America turned back in on itself when manifest destiny had reached its geographic limit. Whether or not Lynch was directly inspired by this film, it feels so Lynchian for how effectively it portrays an America where something deeply wrong lurks under the surface. It’s as if there are centuries worth of dead bodies about to rise from their graves.