Our disdain for artists brought us here

It didn't start with OpenAI's latest insult

If you’ve been on the fence about the utilty of generative AI, there’s a strong chance that events during the last week have pushed you firmly into the ‘against’ camp (welcome). Anyone who’s spent much time online will have been assaulted by an influx of slop generated by ChatGPT’s ‘Studio Ghibli’ filter. I’m not going to post any of these here because I’m not sure the drywall in earthquake-prone apartment can survive the pummelling I will give it if I have to look at more of this crap.

This is obviously complete anathema to the intentions and politics of the filmmakers whose work is being stolen and fed into the sausage machine. Let’s not forget though, the attack on artists long predates this latest outpouring of AI garbage and speaks to a much longer lasting trend towards anti-artist sentiment.

The new ‘Ghibli’ AI is an insult to life itself

To be clear, most people say ‘Studio Ghibli’ as a kind of shorthand to refer to its most famous figure Hayao Miyazaki. The images being shat out by the new version of ChatGPT are specifically based on the art style of the animated films directed by Miyazaki. I will elaborate below on why this distinction between artist and studio is important.

Miyazaki is a filmmaker beloved by many, including me (My Neighbour Totoro may be my favourite film of all time). He co-founded Studio Ghibli in the 1980s alongside fellow director Isao Takahata (who may be my favourite filmmaker of all time) and producer Toshio Suzuki.

The aesthetic is usually the first thing that viewers are drawn to in Miyazaki’s films. His fantasy worlds are grounded in a kind of pastoralism, a seemingly romanticised depiction of life on the cusp of industrialisation that brings to mind the concerns of other fantasy writers like J. R. R. Tolkien. Miyazaki populates this world by drawing from disparate places: Japan and Europe, history and sci-fi and fantasy, utopia and horror, often all at once. This aesthetic is so compelling that it’s no wonder that people latch onto it and so many online have adapted it as their own kind of ‘cottage core’ centred around ‘Studio Ghibli food’ or lo-fi remixes of Joe Hisaishi’s scores.

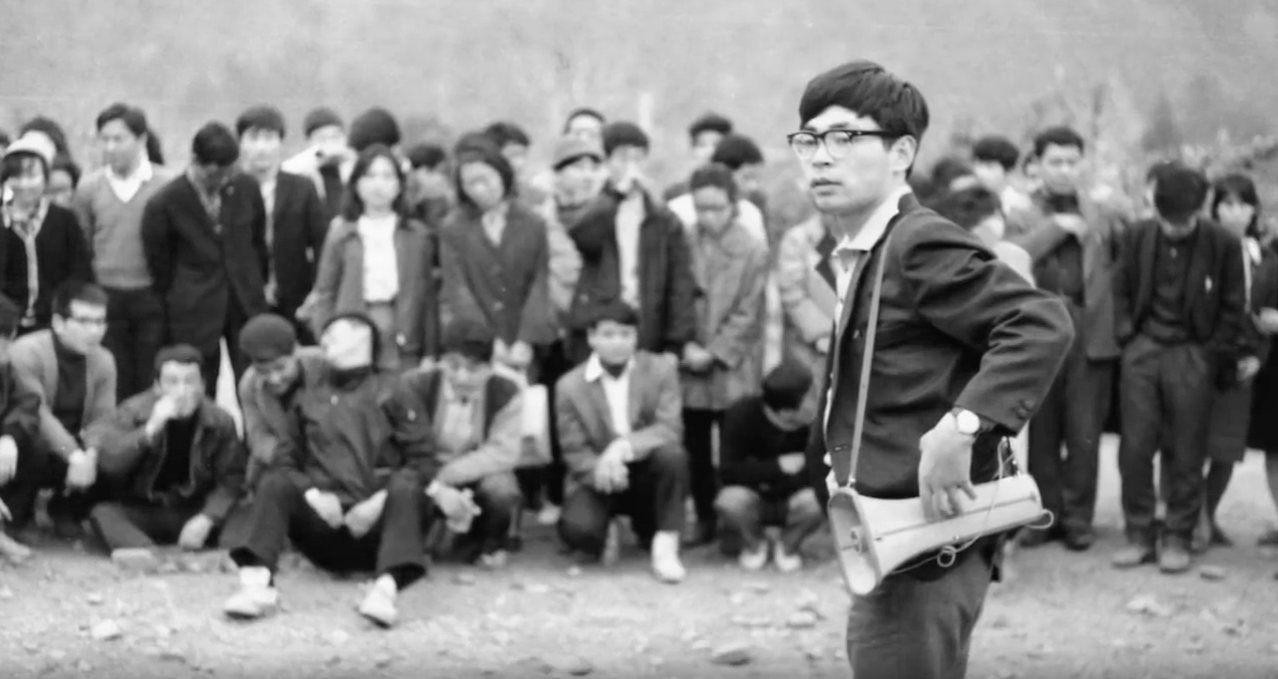

But there is much more going on in the films of Miyazaki than just cosy vibes1. One thing that often gets elided by this fetishisation is, in contrast to other pastoralists like Tolkien, Miyazaki is an explicity left-wing filmmaker. He first met fellow Marxist Takahata when both held positions in the Toei labour union in the 1960s, General Secretary and Vice President respectively. Left wing themes are central to the work of both directors. It’d hard to watch any film Miyazaki has directed and overlook the fact that he is a feminist, an environmentalist and staunchly anti-war. This is a guy who boycotted the 2003 Academy Awards when he won for Spirited Away out of moral disgust at America’s prosecution of the war on terror. It’s no stretch to assume that when he won a second time, for The Boy and the Heron, his no-show was likely motivated by the Gaza Genocide.

Miyazaki is also a guy who is deeply sceptical about modern ideas around technology being positive in and of itself. An ambivalence towards the idea of ‘progress’, especially when that progress comes at the expense of people or the environment, can be found throughout his work. When presented with a prototype of an AI programme, used to animate a zombie in 2016, he famously had this to say:

I can't watch this stuff and find [it] interesting. Whoever creates this stuff has no idea what pain is whatsoever. I am utterly disgusted. If you really want to make creepy stuff, you can go ahead and do it. I would never wish to incorporate this technology into my work at all…

…I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.

So for a right-wing billionaire like OpenAI’s Sam Altman to steal from Miyazaki’s aesthetic to generate images in support of Donald Trump, it adds injury to this insult.

And this kind of thing has been going on for ages.

A brand is not an artist

Sometime in the last few years, people stopped talking about filmmakers and started talking about production and distribution companies: A24, Marvel, Pixar. The auteur theory, the reductive but occasionally useful idea that the best directors can be seen as the authors of their films has been replaced by something much dumber: capital as author2.

All of these companies have ‘house styles’. A24, for example, acquires films that fit its brand identity. But this identity is less about the substance of the films and more about how they can be sold to audiences. Last year’s Heretic and I Saw the TV Glow have little in common with one another except for the fact that they both roughly fall under the definition of “elevated horror”3.

And it’s within this context that people have stopped talking about Miyazaki or Takahata or any of the other artists who have contributed to these films and started talking about them as a brand, a product, ‘Ghibli™’. It brings to mind the dystopian future in David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas where films are called ‘Disneys’.

Like any studio, Ghibli has a ‘house style’. The animated films it has released tend towards the fantastical and the environmentalist. At their worst (and there are quite a few Studio Ghibli films that aren’t any good), they can feel like cheap imitations of Miyazaki4. At their best, they are genuinely affecting artistic achievements. Think of 2016’s The Red Turtle, a Dutch film co-produced by the studio that doesn’t look like ‘Ghibli™’ but which allowed completely different artists to put their unique spin on similar themes.

Then there’s Isao Takahata who sadly passed away in 2018. Unlike Miyazaki, Takahata varied his art style considerably throughout his career. My favourite, Pom Poko, follows a group of tanuki (Japanese raccoon dogs) who are drawn completely differently depending on the context.5 Based on a comic book, My Neighbours the Yamadas is drawn in a way that resembles the source material. By the time of his final film The Tale of Princess Kaguya, the filmmaker had moved away from traditional cell animation into something much less constrained and more painterly6.

But when uncreative losers like those who use ChatGPT talk about ‘Ghibli’, they aren’t talking about Isao Takahata. Takahata’s style is so varied, it can’t be distilled into AI slop. Tech utopianists favour filmmakers with a style that is broad and consistent enough that it can be flattened into a product and squeezed out for mass-consumption. Filmmakers like Tim Burton, Wes Anderson and Hayao Miyazaki. That’s not to denigrate artists with a consistent style7 but to say that their style makes them more susceptible to being turned into a brand.

My Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

If any of this makes you as queasy as it makes me, I implore all of you to shun generative AI, especially when it claims to generate ‘art’. It represents an acceleration of the anti-art sentiment that has been ascendent in the last decade or so. Of course, all AI-generated images look terrible but the purpose of AI isn’t that the output will be ‘good’. Companies like OpenAI are banking on the fact that we will have devalued art so much that audiences are conditioned to see these images as ‘good enough’. And if a robot can make an image that audiences accept, that gives a bunch of production companies licence to start cutting personnel costs.

Every soulless robot is my mortal enemy and should be yours too.

and let’s be honest, there’s more than a hint of orientalism in the idea that these films are just ‘vibes’ ↩

now being superceded by the even dumber idea of art without any human author whatsoever ↩

itself a branding term used to imply that horror only started being smart ten years ago ↩

there is an element of tragedy in the fact that one of the worst filmmakers in the Ghibli stable is Hayao’s own failson Goro Miyazaki ↩

a more ‘realistic’ style if they’re being watched by humans, a traditional anime style when they are interacting with each other and a very simplistic style if they are experiencing pain or heightened emotion ↩

last year’s documentary, Miyazaki and the Heron contains a devastating motif in which Miyazaki believes his old friend is haunting him because he refuses to truly challenge himself artistically ↩

OK, maybe I do want to denigrate Tim Burton ↩