The Activist Canon: Pom Poko and resisting hopelessness

How can you keep fighting the tanuki war when you've lost the tanuki battle?

This is the third entry in my ongoing series on films about organising and what lessons they can teach us about activism. My own experience organising is one of constant learning and films like these help me to reflect on the landscape.

Last time I wrote about Two Days, One Night, the Dardenne Brothers’ masterpiece about building power with colleagues.

“Want to know what it is? My raccoon pouch!”

Before I delve into Isao Takahata’s 1992 praxis anime, I need to address the elephant in the room. Among the films of Takahata (and compared to those of his Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki), Pom Poko is treated as an oddity, especially in the West. There’s a reason for this.

I am, of course, referring to the scrotums.

The tanuki at the centre of the film are a species of Japanese canid that superficially resemble racoons. Tanuki are important trickster figures in Japanese folklore, possessing shapeshifting abilities that are often contained in their pendulous testicles. Americans tend to avoid broaching foreign concepts like ‘tanuki’ or ‘testicles’ with their children so many subtitled and dubbed versions of the film use the term ‘raccoon pouch’ (even though they aren’t raccoons and neither raccoons nor tanuki are marsupials). This cultural specificity has made this film a hard sell outside Japan and serves as yet another example of Westerners fixating on the most surface-level details in Studio Ghibli films while ignoring their politics. It is a massive disservice to one of my favourite artists that Pom Poko is rarely read as an activist film.

So yes, this is a film about a group of magical forest creatures who use their genitals to fight back against the destruction of their habitat. Please brace yourself with a fainting couch when you watch (or rewatch) the film, available on a number of streaming sites.

“You think that will stop the developers? Don't just frighten them. We need to hurt them. Inflict some serious pain!”

The thing that stands out to me about Pom Poko as a depiction of activists is that their struggle is ostensibly unsuccessful.

Despite its fantasy framing, the film is set against the backdrop of real historical events: the creation of housing developments in the Tama Hills near Tokyo in the late 20th Century. This development actually went ahead. Humans created more housing for themselves at the expense of the creatures who lived there before them. Many of those humans would end up watching the movie. This is the story of a struggle already lost.

Pom Poko takes a birds-eye view of the tanuki community across a period of several years. There is a central character in young tanuki Shokichi but the film doesn’t stick to his point of view. Takahata’s perspective moves freely between different tanuki characters, even occassionally checking in on humans and kitsune (magical foxes that share tanuki’s shapeshifting abilities). With a narrator providing historical context and the art-style changing to fit the scene, it often feels like a documentary.

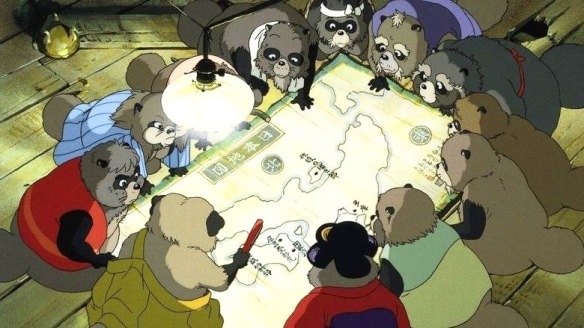

This perspective allows the film to cover a lot of ground. Anyone who has spent any amount of time in activist circles1 will recognise the endless meetings where strategy and tactics are argued at length and rarely resolved. One of the best things about Pom Poko is that it doesn’t judge the tanuki for their own theories of change. Even Gonta, the most aggressive member of the community and occasional rival of Shokichi, remains sympathetic as he argues for killing the humans who steal their land. The right tactic is whichever one works best.

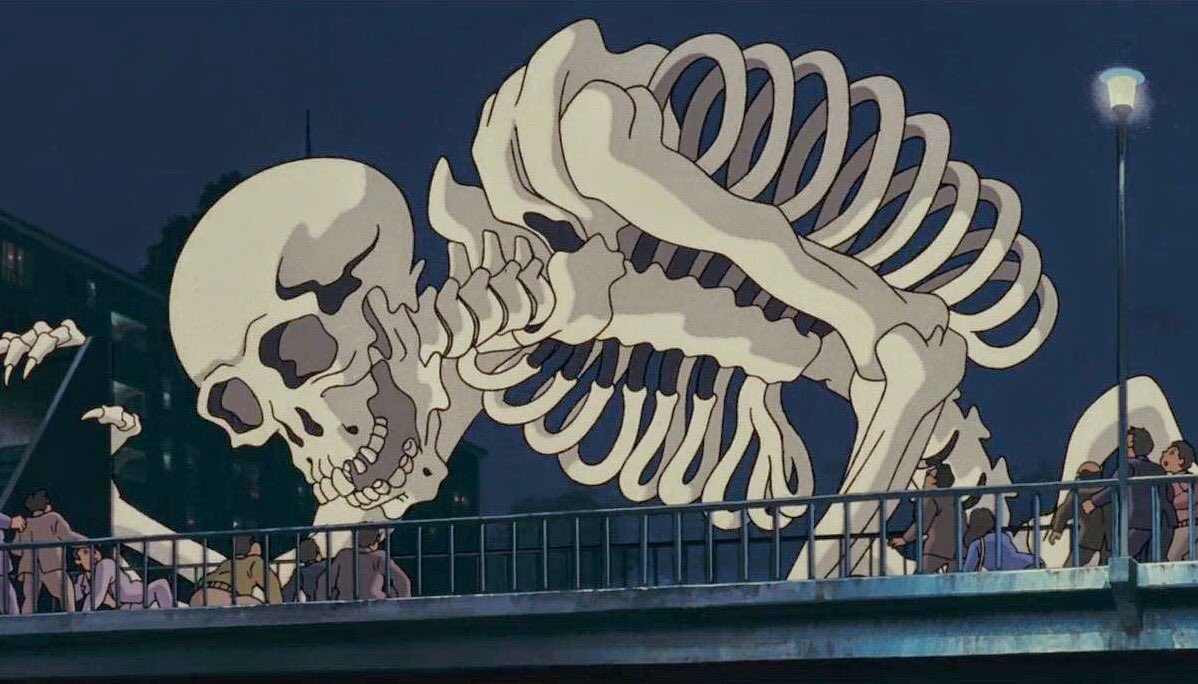

Gonta represents one end of the ideological spectrum but his method is simply one among many the tanuki attempt throughout the film. These sit in dialectical relation to one another, sometimes (but not always) contradictory. Shokichi tends to favour methods that scare the humans without harming them, culminating in one of the film’s most glorious sequences, a ‘Yokai Parade’2 through the city. Maybe if the humans think the Tama Hills are haunted, they’ll leave the tanuki alone. Others want to learn from their elders, travelling long distances to recruit powerful tanuki like the legendary Transformation Masters of Shikoku3.

As the tanuki organise, life goes on for them. They grow up, fall in love and have pups, increasing the pressure on the dwindling food supplies.

“What if our little pranks aren't doing any good at all?”

The debates among the tanuki inevitably lead to discussions around compromise. To what extent can the tanuki live alongside humanity? Humans may threaten their environment but they also bring food like tempura and creature comforts like television that appeal to an animal often defined by its gluttony and laziness. Some of the tanuki are tempted by the possibility of using their abilities to live among the humans but not all tanuki possess the power of transformation. Should this community look after its most vulnerable members or just let them die?

As the film goes on, none of the methods have the desired result. The development continues at pace even as Gonta succeeds in killing some of the humans. An amusement park takes credit for the Yokai Parade, neutralising its impact. A group of kitsune are successful in tempting a few of the tanuki into ‘selling out’, effectively abandoning their non-magical comrades. Even the Transformation Masters with their impressive abilities struggle to push back against the march of ‘progress’.

So the Tanuki lose. Gonta leads his hardliners in a violent kamikaze mission, killing a good number of cops with their ballbags before falling to the batons. Some of the tanuki go directly to the media, pleading in vain for their lives. The 999 year-old Transformation Master Dazaburō enlists the non-transforming tanuki in a doomed cult. In the film’s most bittersweet scene, Shokichi works with his magical comrades in one last action, not to scare the humans but to show them what the hills looked like before urban encroachment, reminding them of what they’ve lost.

The film ends a few months later, with Shokichi and his wife resigned to a life in which they go undercover as humans and work boring human jobs. On his way home from the office, he hears the oddly familiar sounds of celebration. He follows the music and finds a group of his non-transforming comrades partying in a golf course, shedding his salaryman disguise to join the party. Even in the face of defeat they have found a way to keep going.

“The only way this makes sense is if all you humans are tanuki! You're all stupid, evil, selfish tanuki!”

In case you haven’t realised, the tanuki are us. They’re selfish and lazy and greedy. They disagree and argue. They love and they lose and they find joy in the face of defeat, just like us. It’s no secret that, before the film even starts, they’ve failed to stop the Tama Hills development.

You can choose to read their struggle through the lens of environmentalism, the defence of Indigenous land or the rights of the homeless. Their movement looks a lot like ours in its competing factions and uncertainty about what’s actually going to yield results. Anyone who’s ever fought for any of the above knows what it means to lose and knows why the fight must continue anyway. Discussions around the utility of violence and compromise and political messaging become second nature. Even when we win, we know that our political enemies will never acknowledge it, just like the humans taking credit for the Yokai Parade. Last year’s Hīkoi almost certainly played a role in killing the Treaty Principles Bill but though the government would never acknowledge it.

The tanuki who survive Pom Poko have faced down the end of the world as they know it and they still find ways to express joy. Fatalism is never an option. We owe it to all those who have gone before us to keep fighting, even if things feel hopeless right now.

Johnny’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Takahata, like Miyazaki, was a lifelong radical, involving himself in causes related to environmentalism, labour rights and feminism ↩

This sequence is packed to the gills with references to Japanese folklore and characters from other Ghibli films (most notably Totoro) ↩

Inspired by important tanuki figures from traditional stories ↩