The Gallipoli Myth (Part 2)

When former opponents agree on a narrative

This is Part 2 of a pair of articles about the way narratives surrounding the Battle of Gallipoli are co-opted for nationalist purposes. Last week’s article focused on Turkish nationalism while this one looks at the way the myths are used to downplay ANZAC war crimes.

Another perspective on the ANZACs

I started last week’s piece by referencing a film set during the Battle of Gallipoli that casually reinforced Turkish nationalist ideas. This week, I’d like to contrast it with another movie set during the same battle.

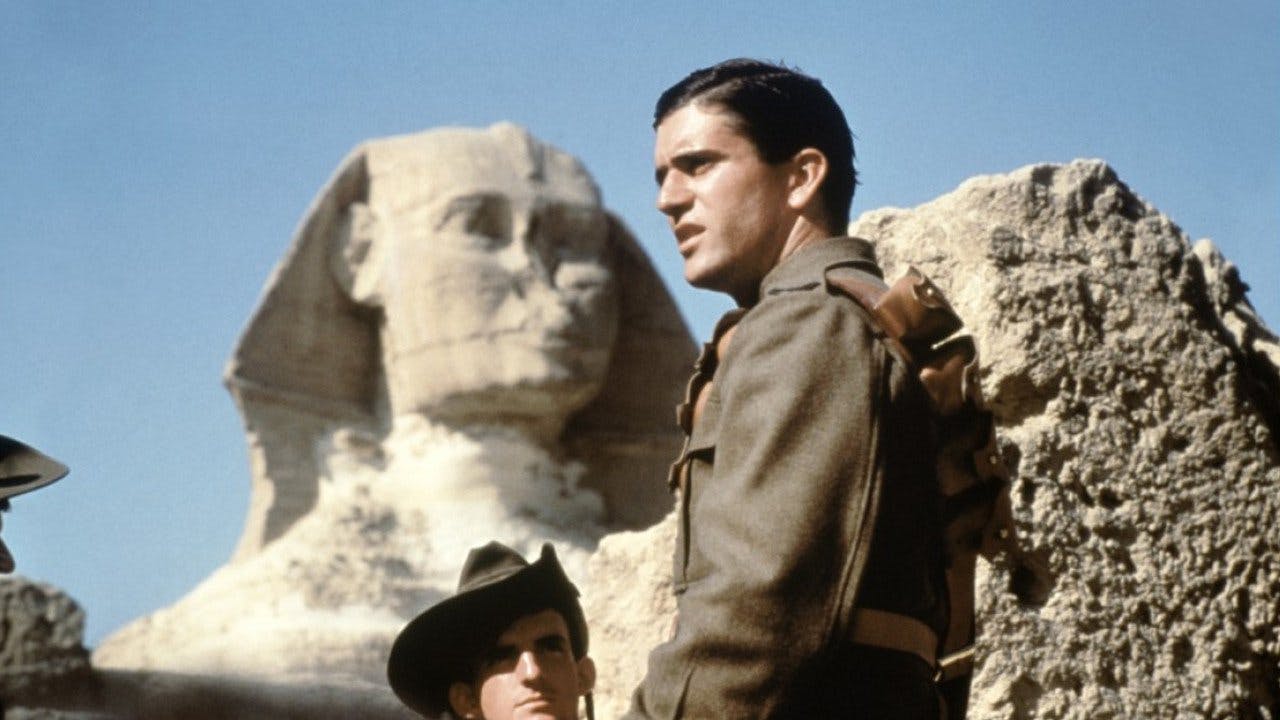

Peter Weir’s Gallipoli (1981) follows a couple of Aussie lads (played by Mel Gibson and Mark Lee) on their journey from the Western Australian outback to the titular battle. It takes its time getting to the Dardenelles with most of film taking place in Australia and Egypt respectively. This middle section includes scenes of the boys wrecking havoc on North African locals. They tease children, patronise sex workers and even ransack a shop after they (wrongly) suspect a merchant of ripping them off. The point-of-view stays with the ANZACs and these scenes retain a lighthearted tone as a way to contrast them with shit getting real at Gallipoli. However, it is clear that the events would have been anything but lighthearted for the reluctant hosts.

I bring this up, not to frame Gallipoli as some sort of exemplary depiction of the British Empire’s soldiers in the Islamic world1 but I was surprised at how much the narrative has shifted in the decades since. The film distinguishes between Arab civilians and the Ottoman Empire and doesn’t feel the need to affirm the imperialist narratives of the latter. I would describe the film’s position as a broad opposition to all imperialism (British and Ottoman) for the way it impacts ordinary people (ANZACs, Arabs, even Indigenous Australians). This is a world away from the current moment where affirmation of imperialist points of view, British and Ottoman, is common.

Johnny’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

ANZACs in the Islamic World

The central instinct of We Are Still Here to emphasise the way Indigenous peoples were impacted during the First World War is completely justified. The problem in its execution is that, by treating the Ottoman Empire as Indigenous, it ignores the colonial violence the ANZACs were actually inflicting.

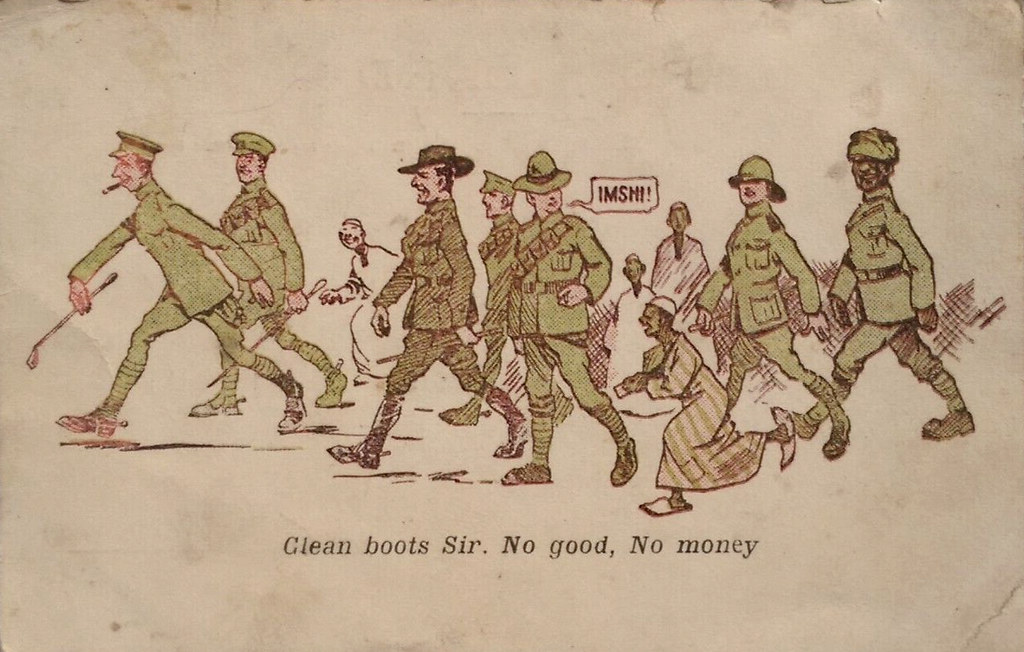

In 2021, I attended a National Library talk by New Zealand Defence Force Historian John Crawford (no relation) on the 1915 Senussi Campaign in Libya. In this talk, Crawford explained that “the worst incidences of crime against other groups by New Zealand personnel all relate to Arab civilians, not to Ottoman military personnel.” He elaborated on the way that New Zealand’s activity was driven by “a pronounced feeling of racial superiority over Arabs in general.” This is the same racism that is casually depicted in Weir’s film. Attitudes towards the Ottomans were simply not motivated by racism to the same extent. The Turks were viewed as more-or-less European2 and that has made it easy to frame them as a noble opponent in the centuries since then.

The same cannot be said for the non-Turkish peoples of the Middle East and North Africa.

At Senussi, New Zealand soldiers likely killed a number of Arab non-combatants but it is far from the only example of violence inflicted against civilians in the region. Maybe even more famous is the ‘Surafend incident’ in 1918 in which ANZAC soldiers massacred a number of Palestinian men after the official end to hostilities3. The century since then has included several instances of New Zealand military involvement in the Islamic world. From the North Africa campaign of the Second World War4 to our shameful actions in Malaya and Afghanistan to our current complicity in Israel’s genocide of Palestinians, we have often protected the interests of Empire from the ‘threat’ posed by Muslim civilians in the Middle East, Africa and Asia.

In this wider historical context, it seems simply obfuscatory to build our national identity around the one time we got our asses handed to us by an imperial enemy who just happened to be Muslim. But the obfuscation is the point. In the exact same way as Türkiye, New Zealand loves to commemorate the Battle of Gallipoli specifically because of how it distracts from all the other evil shit we were doing at the time. The narrative serves both sides.

Our changing political memory

On Friday, I attended the Pōneke Anti-Fascist Coalition’s ‘Never Again’ ANZAC Day peace picnic. The quality of speeches was extremely high and emphasis was placed on both the Armenian genocide and the Surafend massacre.

A couple of speakers discussed the way that people who experienced the world wars are more likely to have nuanced views on overseas military action. Wajd El-Matary from Justice for Palestine spoke about her childhood piano teacher, a New Zealander whose memory of the Second World War influenced his own opposition to the Nakba. This might seem counter-intuitive to anyone who believes in some sort of linear progression of history where each generation is less racist than the last but it is consistent with my own coversations with older friends and family. I find that my grandparents’ generation tends to have an innate opposition to Zionism that isn’t shared by Baby Boomers and Generation-Xers. As we move further from the World Wars, the Holocaust and the Nakba, the collective memory of these events becomes easier to warp.5

This can be seen in the changing status of ANZAC Day in the last century. Although I am speaking from a New Zealand perspective, I can’t imagine that the ambivalence towards war expressed by Weir’s Australian film in the early-1980s would have been especially controversial on this side of the Tasman. It came at the tail end of a period in which ANZAC Day was repeatedly the target of protests. It wasn’t until the subsequent decades, including the 75 and 100-year anniversaries of the Battle of Gallipoli, that commemorations became more straightforward in their unconditional support of our beautiful boys. There are likely various explanations for this shift but I would guess that it’s some combination of War on Terror jingoism, an increase in Turkish Nationalism (especially under Erdoğan) and the loss of more and more people who remember the atrocities of the first half of the 20th Century. I’m deeply embarrassed by the fact that this has resulted in my generation being much more accepting of nationalist narratives around ANZAC Day.

A lie agreed upon

The First World War was a senseless loss of human life inflicted by Europe’s imperial powers (including the British and Ottoman empires) on ordinary people who had the misfortune of being subjects of their territories. This includes Arab and Armenian victims of racialised violence as much as it does the ANZACs who were lured to the other side of the planet for a stupid cause. It laid the foundations for the subsequent century of further racialised violence inflicted in Europe, Palestine and across the globe.

But that’s not the way we talk about it.

For Turkish and New Zealand propaganda, the Battle of Gallipoli takes on undue historical importance that allows it to eclipse all of the historical context surrounding it. This suits Türkiye because it distracts from its own genocidal actions and gives it legitimacy in the eyes of international allies. But it also suits conservative New Zealand narratives. We don’t want to acknowledge our own complicity in crimes against humanity, we just want to send our people on holidays to the Dardenelles to (mis)remember history. And the further we are in time from what came before, the easier it becomes to iron over history’s less pleasant wrinkes.

Johnny’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

It should also go without saying that Peter Weir is one of the best Aussie directors of the late 20th Century and even one of his less-talked-about film like Gallipoli is gorgeous. ↩

Albeit, “the sick man of Europe”. ↩

When thinking about the violence of 21st Century Zionism, it’s important to situate it in its appropriate historical context. Just as it didn’t start on 7 October 2023, it also didn’t start with the Nakba in 1948. New Zealanders have been complicit in colonial violence against Palestinians for well over a century. ↩

Reminder that you do not have to hand it to Rommel! What is it with New Zealanders and trying to make excuses for the genocidal forces we fought in the world wars?! ↩

This idea was taken to farcical extremes when Wellington Mayoral Candidate Ray Chung tried to get a ‘No Nazis’ sign removed. One would think this is a relatively uncontroversial political statement on ANZAC Day. ↩