The Phantom Carriage

Day 17 of my 31 Days of Horror viewing

For the last few years, I have used October to give myself a viewing assignment: a different horror film each day. Now that I have escaped the real life horror of New Zealand’s public service, I intend to write a piece inspired by each film.

My seventeenth film is Victor Sjöström’s The Phantom Carriage / Körkarlen (1921).

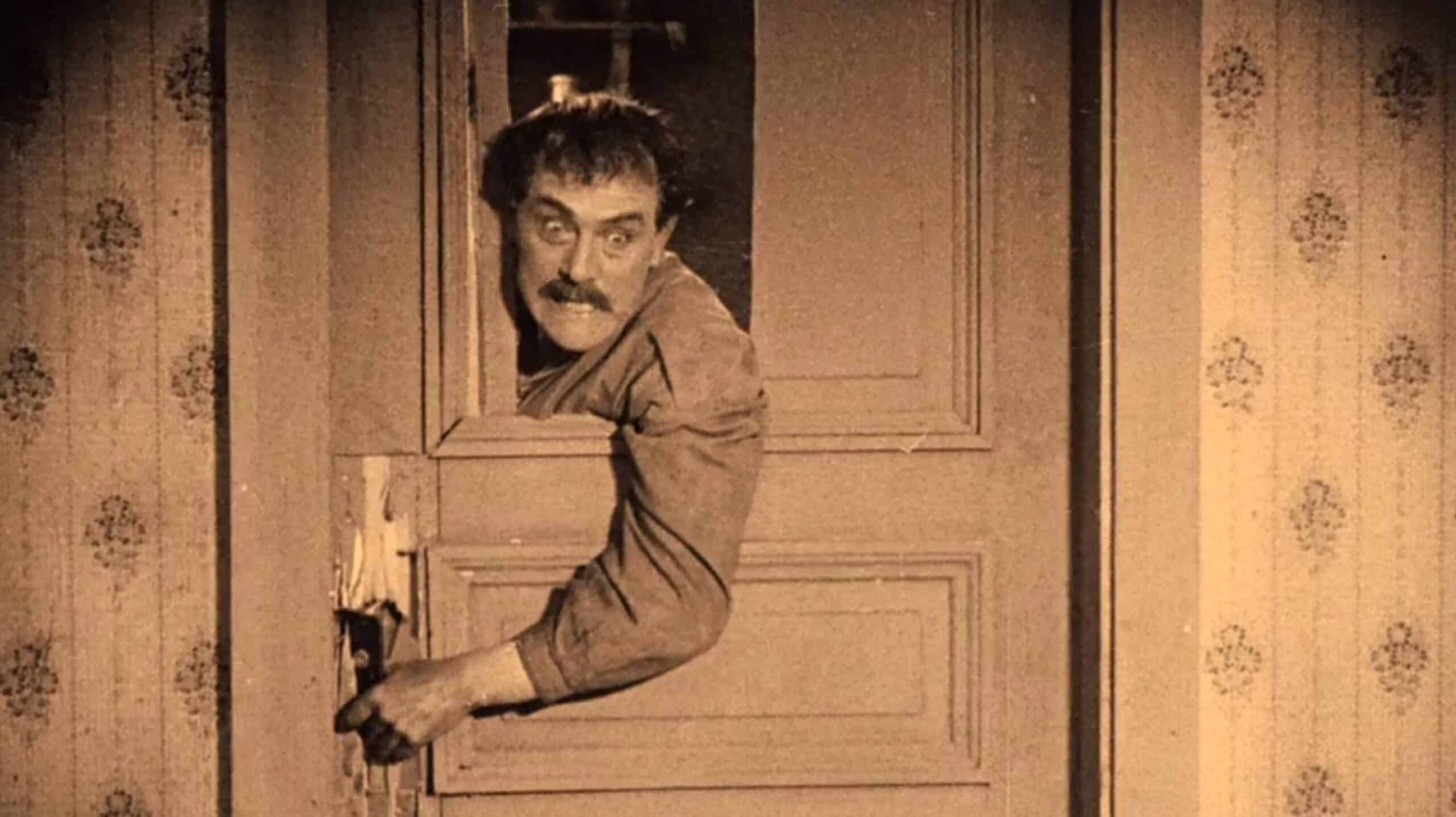

When I think of the most effective imagery in the history of horror cinema, a decent chunk of examples come from the silent era. Films like Faust, Häxan and (my fave) Nosferatu have scenes that come across as completely uncanny due to filmmakers who were experimenting with the form and not-yet constrained by the limitations of sound recording. This is why Francis and Roman Coppola so effectively drew upon these techniques in their Dracula. That these films are a century old only adds to this feeling— there’s something weird and alien about a silent horror film that makes you feel like you’re watching the videotape from Ring.

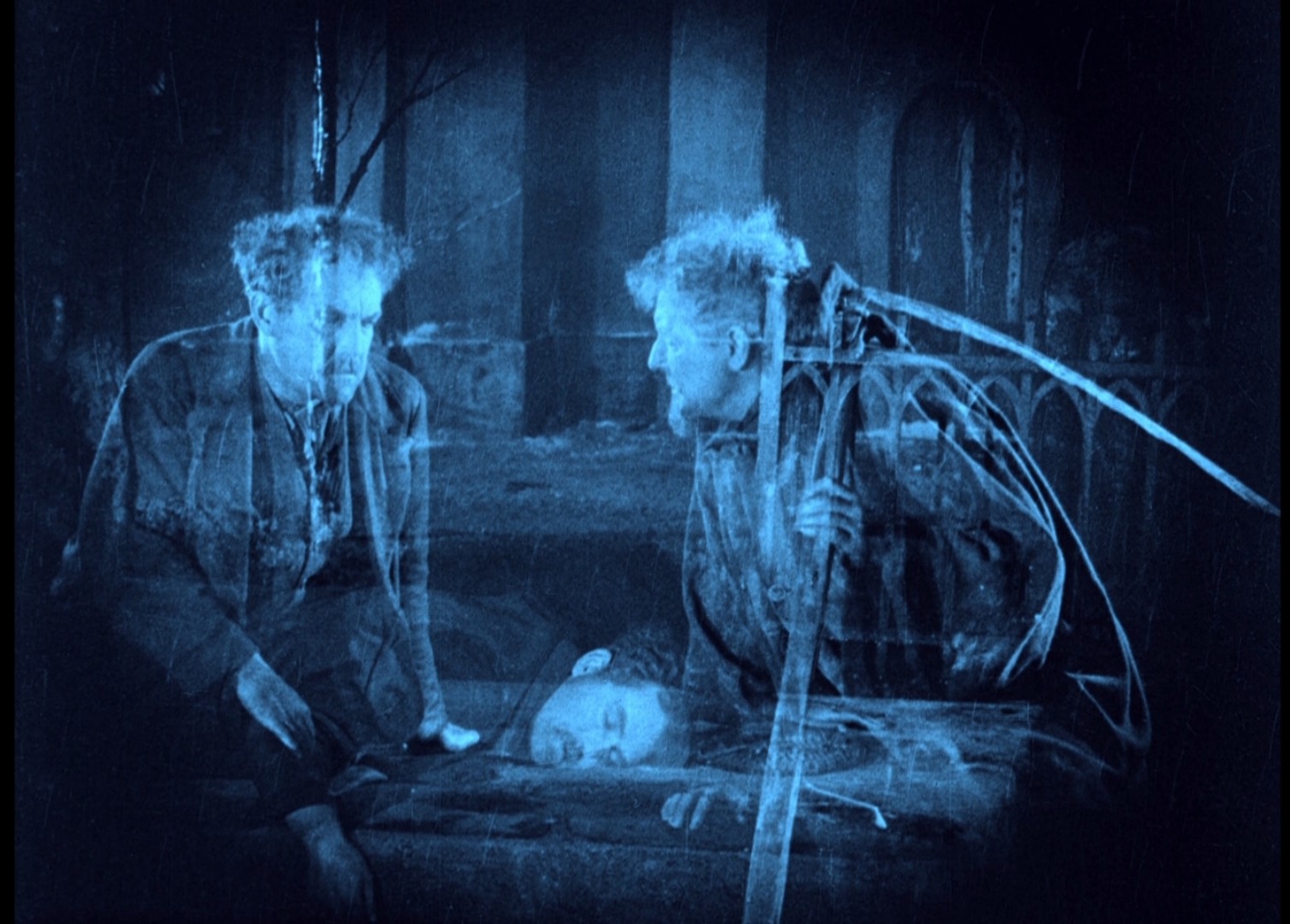

The Phantom Carriage, based on the 1912 Swedish novel Thy Soul Shall Bear Witness!, uses this type of imagery to great effect. In particular, Sjöström employs super-imposition to allow its the titular carriage and the spirits of the dead to glide across the screen. They occupy the same frame as the living but not the same realm.

On New Year’s Eve, protagonist David Holm (played by the director himself) tells the story of the Phantom Carriage. It is said that the last person to die before the clock strikes midnight each New Year’s Eve, is cursed to drive the carriage for the subsequent year. The year will feel like an eternity for the driver as they collect the souls of each person who dies.

The drunkard David is unaware of the fact that the current driver is his old friend Georges (Tore Svennberg), the man who initially told him the story, nor that he is in line to become the new driver. After the ghostly Georges confronts David, the bulk of the film is dedicated to flashbacks and flashbacks-within-flashbacks to David’s sorry life. David is reminded of the way he mistreated his wife Anna (Hilda Borgström) and their two children. Throughout his struggles, Salvation Army Sister Edit (Astrid Holm) tried in vain to set David on the right track.

The Phantom Carriage sits firmly in the tradition of stories about dudes being confronted about their past by supernatural figures. David lived such a wretched life that he’s definitely more of an Ebenezer Scrooge than a George Bailey. Such a decent chunk of the film’s runtime is spent on these flashbacks that I was rooting for that ghastly carriage to come put him out of his misery. It’s definitely in the tradition of severe, protestant austerity that I associate with Scandinavian cinema and that filmmakers like Ingmar Bergman and Carl Theodor Dreyer would elevate. The source novel was intended to educate the public about consumption and that didactic approach is reflected in the film’s morality and its elevation of the Salvation Army.

You will be relieved to hear though that by the end of the film, David sees the light, learns to follow the example set by the Sallies and is saved from The Phantom Carriage. Along the way, the audience is treated to a morality lesson and some of the most effective silent film imagery.